Financial stability risks could arise if banks and investors all take the same route to decarbonize their portfolios

“When the herd moves, it moves.” UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson used this phrase in his July 7 resignation speech to describe how political support flooded away from him in the wake of one too many scandals.

It is also apposite in the context of financial markets. Herd behavior is the bane of investors and a major preoccupation of regulators. Shifts in investor sentiment — suddenly over the course of a few hours or gradually over a longer time span — can cause asset values to swing wildly and financial institutions to implode. Just look at the fallout from the recent collapse in cryptocurrencies.

Smart thinkers are now taking an interest in how herd behavior could amplify climate risks and derail the low-carbon transition. In a recent speech, Anil Kashyap, an external member of the Bank of England’s (BoE) Financial Policy Committee, touched on the macroeconomic dangers that could arise if financial institutions executed similar low-carbon transition plans.

Specifically, he claimed that if every bank and investor cut off financing to carbon-intensive producers “indiscriminately and too quickly” then the UK economy would suffer. He also warned that it would be impossible for every financial institution to expand their financing of climate-friendly assets at the same rate and time, citing “immutable constraints on the speed at which green forms of energy production can be ramped up.”

Summing up, Kashyap pointedly asked institutions: “if other banks and insurers are expecting to carry out the same strategic changes to their businesses that you are, would your planned response to climate risk still be a workable/sensible one?” The answer, presumably, is: “no.”

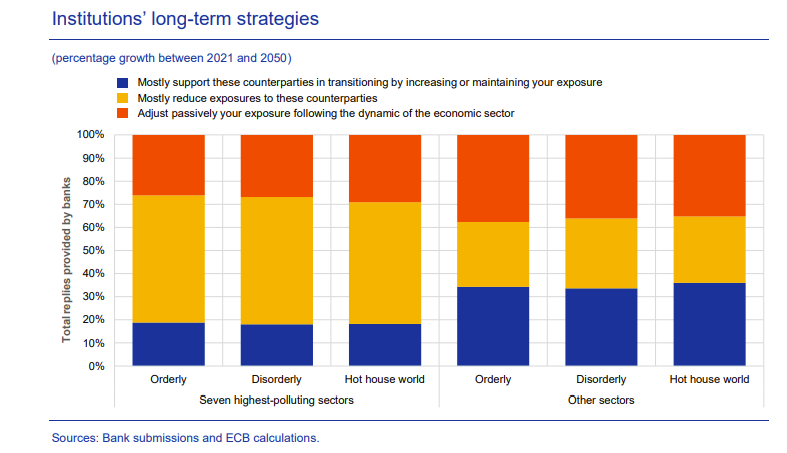

In Europe, banks’ transition plans evidence this herd mentality. As part of its recent supervisory stress test, the European Central Bank (ECB) asked participants what their long-term strategic plans would be under three different climate scenarios: an orderly transition, a disorderly transition, and a hot house world. “Banks consistently reported the same strategic options regardless of the scenario analysed,” the ECB reported. Put simply, they all elected to reduce their exposure to polluting sectors while continuing to support less carbon-intensive activities.

This shows that banks lack imagination when it comes to responding to different climate outcomes, which may be a side effect of them not thinking carefully about various transition pathways in the first place.

Herding itself could also catalyze transition risks. In the worst-case scenario, one echoed by Kashyap, banks with copycat transition plans would all adjust their portfolios over time in unison, pumping up the price of ‘green’ assets to fragile, bubble-like proportions while eviscerating the value of ‘dirty’ investments. While each lender would redirect their own capital this way in pursuit of an orderly transition, together their actions could bring about the conditions that lead to a disorderly one, with painful consequences for the financial system as a whole.

The dichotomy of green and dirty investments may be part of the problem. In a recent article in the Financial Times, Huw Van Steenis, co-chair of World Economic Forum’s finance council, wrote that a shift in focus toward “khaki finance”, also known as “transition finance”, may help reset current thinking on how the financial sector can best facilitate a low-carbon future.

This means destigmatizing the financing of dirty industries that have sound plans to go green. The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) is taking the lead on this front. In its recent framework for financial institution transition plans, the alliance identified “financing or enabling the transition of real-economy firms, according to robust net-zero transition plans” as one of four ways that banks and other financial firms could support real-world emissions reductions.

Of course, the danger with khaki finance is that it lacks a universally respected definition. This could allow unscrupulous lenders to prop up climate-harming businesses under the guise of aiding the transition. Other khaki assets may be linked to companies that are legitimately taking steps to decarbonize, but at too slow a pace to stop transition risks from impairing their value — inflicting losses that some banks may be ill-equipped to bear. Again, GFANZ is attempting to address these risks by laying out what credible real-economy transition plans look like on a sector-by-sector basis.

If these concerns are addressed, then widespread adoption of khaki finance could give banks more flexibility to create different sorts of transition plans, reducing the risk of herding while still ensuring each firm takes steps toward the same low-carbon goal. Under this scenario, capital would flow into a broader array of assets, which should stop green bubbles from forming and prevent a precipitous collapse of dirty investments.

However, the intense pressure exerted on banks from myriad external stakeholders could also catalyze different sorts of financing dynamics. When it comes to green or khaki assets, certain lenders may choose to act on the wisdom of the fictional financier John Tuld from the 2011 movie Margin Call: “Be first, be smarter, or cheat.”

One way this could manifest is by first movers snapping up prime green assets and shunning khaki and dirty investments altogether, in order to differentiate themselves from the pack. Small, socially responsible institutions like Amalgamated Bank already eschew all kinds of fossil fuel investing and prioritize green lending. If certain larger banks follow suit, they could crowd out access to the most creditworthy green assets, leaving their rivals to pick through the dross. This strategy would maximize their upside in the event of an orderly or disorderly transition, and alleviate their reputational risk to boot. After all, a ‘pure green’ bank wouldn’t have to painstakingly explain why its khaki investments aren’t greenwash — because it wouldn’t have any.

Smart banks, with the budgets to acquire an information advantage in climate investing, could also monopolize prime khaki assets in the same way. Certainly, the pool of khaki assets is larger than that for green investments, but their quality — in terms of climate-friendliness and creditworthiness — is more widely dispersed, too. A Darwinian sorting of khaki assets in this manner could lead to a redistribution of transition-related credit risks and climate reputational risks from big, smart banks to smaller, dumber ones. This may not be the worst outcome for financial stability, since large, internationally active lenders pose the greatest systemic risk to the system. But in the long term it could force many smaller banks into distress and result in a greater consolidation of banking assets among the ‘too big to fail’ lenders/

The “cheat” option could be much more damaging to the financial system, not to mention the low-carbon transition itself. The BoE’s Sarah Breeden made this point at a recent conference. She argued that if green labels are heedlessly applied to climate-harming investments then trust in the financial system as a facilitator of the low-carbon transition would be undermined.

It’s likely the same risk would materialize following the mislabeling of khaki assets, too. Though Breeden did not elaborate on the possible consequences of this loss of trust, one outcome could be an acceleration of disintermediation in financial services. This in turn could channel credit, market, and transition risks towards entities that are ill equipped to shoulder them.

The ECB offered a different perspective on the same greenwashing risk in its latest Financial Stability Review, arguing that “it could lead to an undervaluation of transition risk and to potential fire-sales of green bonds.” Similarly, a bank could lend to companies with dubious climate credentials but which nonetheless manage to acquire a green seal of approval from a third-party verifier or regulator-backed investing taxonomy. The bank may do well off this subterfuge for a time, but as the low-carbon transition picks up pace its loan-losses would likely grow too.

Another way a bank could pull the same trick is by packing dirty investments into green securitizations. The fluid standards applied to these kinds of instruments could make this kind of cheating attractive. Just recently, the International Capital Markets Association, a major standard-setting body, published updated definitions for different kinds of green instruments. Notably, the definition of a “Secured Green Bond” would allow a green securitization to be underpinned with non-green collateral, so long as the money raised through its sale was used to bankroll climate-friendly activities. This kind of standard could facilitate a sort of financial alchemy that turns dirty or khaki investments into pure green assets.

Herd behavior can be ruinous. Just ask Boris Johnson. In the context of financial stability and the climate transition, it could prove catastrophic. However, efforts to ameliorate herding across financial institutions’ transition plans should not incentivize other kinds of dangerous behavior. Specifically, external stakeholders must not inadvertently vivify the mantra expressed by Margin Call’s Tuld — especially the part on cheating.