The Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario exercise is over. But the debate over what the results mean for banks, supervisors, and the UK financial system has just begun

All the way back in December 2019, before most of the world had heard of a disease called COVID-19, the Bank of England (BoE) announced it would conduct a Biennial Exploratory Scenario to investigate the climate risks facing banks and insurers — a climate stress test, in other words. The global pandemic put the ‘CBES’, as it became known, on hold, and it was only in 2021 that UK financial institutions actually started the exercise. This week, two-and-a-half years after it was first announced, the world finally got to see the results.

On the surface, these imply that UK banks and insurers are well-placed to weather the rigors of climate change. The BoE said the results show that the costs of a transition to net zero “should be bearable without substantial impacts on firms’ capital positions.” While loss projections varied across firms and scenarios, the BoE said they were equivalent to an average annual drag on profits of around 10-15%. Sam Woods, the Deputy BoE Governor for Prudential Regulation and Chief Executive Officer of the Prudential Regulation Authority, said in a speech on Tuesday that “these are not the kinds of losses that would make me question the stability of the system, and they suggest that the financial sector has the capacity to support the economy through the transition.”

However, scratch below the surface and it’s clear there’s much more to the CBES results than these top-line numbers. What’s more, decisions made over the scope of the exercise — in particular the choice to carve out banks’ trading portfolios and limit counterparty-level analysis to the largest borrowers — mean that the results have plenty of gaps, and likely understate the magnitude of climate impacts on the participants.

The climate risk management landscape has also shifted since the CBES was first announced. Practitioners have grown increasingly skeptical of financial supervisors’ approaches to climate stress testing. Earlier this month, a band of climate risk professionals hosted a roundtable discussion on Real World Climate Scenarios (RWCS) which concluded that “current economic climate scenario modelling is not fit for purpose.” They further claimed that today’s analyses are full of “inappropriate quantification” and do not fully appreciate volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. The roundtable wasn’t full of climate activists, either — it included notables from KPMG, Ortec Finance, and the University of Oxford, among others.

It’s against this backdrop that the CBES results, and any subsequent policy responses, should be considered. Otherwise, there’s a danger that the top-line risk projections are taken as gospel by the UK financial industry, and used to fuel the kind of attitudes recently expressed by HSBC’s Stuart Kirk — that investors need not worry about climate risk.

Before getting into the details of the results, it’s worth recapping the purpose of the CBES and how it was conducted. The objective was to gauge the resilience of financial institutions — and the financial system more broadly — to the physical and transition risks generated under a range of possible climate scenarios. To this end, the BoE secured the participation of the UK’s largest banks and insurers, including household names Barclays, HSBC, NatWest, Aviva, Legal & General, and Scottish Widows. Additional aims of the exercise included helping participants to improve their climate risk management practices and boosting understanding of the challenges climate change poses to their business models.

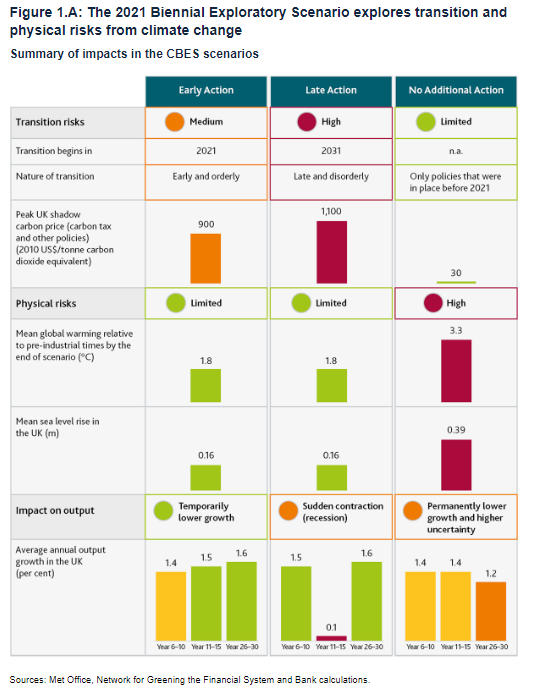

To achieve these aims, the CBES subjected participants’ lending and investing portfolios to three possible climate futures: an ‘Early Action’ (EA) scenario, a ‘Late Action’ (LA) scenario, and a ‘No Additional Action’ (NAA) scenario. The first two scenarios plot different routes to a net-zero-emissions-by-2050 endpoint and were intended to capture firms’ transition risks. The NAA, in contrast, was designed to explore firms’ resilience to the physical risks that may arise if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise. All participants had to assess their resilience to these scenarios over a 30-year horizon.

Source: BoE

The EA, LA, and NAA are all based on scenarios developed by the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), the club of climate-focused central banks and supervisors, of which the BoE is a member. These scenarios have come under attack from climate hawks in the nonprofit sector, notably France’s Reclaim Finance and Australia’s National Centre for Climate Restoration (Breakthrough), which have argued that they fail to provide realistic and low-risk 1.5°C pathways. The RWCS roundtable participants also accused them of shortcomings. One of their number, Mark Cliffe of KPMG, wrote that the integrated assessment models (IAMs) used to generate the scenarios “simply fail to address the VUCA [volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity] issues inherent to climate change.”

On the other hand, the NGFS scenarios represent the cutting-edge of climate risk analysis among the financial supervisory community, and cover nearly 1,000 economic, financial, transition, and physical variables in total. They have also been widely adopted, not only by other financial supervisors, but individual institutions too. Therefore, whatever their flaws it’s fair to say the NGFS scenarios represent the current consensus approach to projecting climate risks to the financial system. In addition, to ameliorate the risk that the scenarios lowballed the scale of climate impacts, the BoE asked participants in a follow up to the initial exercise to assume that their climate risk losses would be double what they initially projected, and describe how their planned management actions would change accordingly.

One other aspect of how the CBES was run is important to keep in mind when analyzing the results. The BoE opted for a ‘static balance sheet’ approach to the exercise, meaning that participants’ loss projections were based on the composition of their portfolios as they stood at the end of 2020. In other words, firms were not allowed to alter their mix of assets and liabilities over the 30-year horizon of the scenarios. As Climate Risk Review has argued before, a ‘static balance sheet’ approach has its drawbacks, not least that it’s unrealistic to assume institutions will not rebalance their portfolios as the economy transforms in response to climate change. However, the upside is that it offers a snapshot of firms’ vulnerabilities in the here and now. This means participants get a sense of how climate-sensitive their portfolios are today, and the size of the changes they would need to make to lower their risk profiles tomorrow.

And so to the results. For brevity, this analysis will focus solely on how banks performed. Though the top-line takeaway is that the projected costs are “bearable”, this lacks nuance. Cumulative losses varied by scenario, with banks projected to shoulder the most losses under the LA. However, the BoE cautioned that the losses under the NAA were likely understated since “banks were less well equipped to assess thoroughly the impact of physical risks prominent in this scenario.”

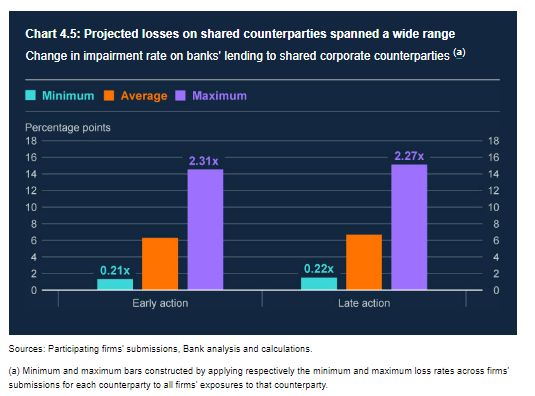

Projected losses also varied lender to lender, suggesting “significant uncertainty around the true magnitude of these risks.” Individual banks’ loss estimates varied wildly even for counterparties they shared in common, explains James Belmont, climate risk lead at consultancy Baringa Partners:

“You have a 10-times difference between the maximum and minimum loss projections, so some banks are making wildly higher estimates of their losses than others. That was inevitable given the freedom that the BoE gave the banks to develop their own modeling approaches in this first, exploratory exercise”

Indeed, by far the most important takeaway from the results is that the projected losses could be vastly understated (or, in some areas, overstated) because of the different ways in which banks approached the modeling challenge — not to mention the poor quality of data used to underpin their estimates. The BoE made this point throughout the results. One section said that the “inability to capture appropriate and robust data in certain areas….means many climate risks are only being partially measured.” Another said banks “struggled consistently to assign their large corporate customers to industrial sectors, which limits the reliability of even their sectoral assessments of potential losses.” In a section on physical risks the BoE also highlighted “the limited availability and sophistication of modelling tools with which to assess non-flood risks at a property level over long horizons.”

The BoE’s willingness to be so open about the level of uncertainty around the CBES’ loss projections is commendable, and stands in stark contrast to the European Central Bank’s rhetoric around its own stress test findings. As Belmont explains:

“The CBES banks recognize that the BoE has done a pretty good job of treating them like adults and saying: here’s the objective, now you have freedom to go out and deliver on this objective. I’d say they’ve done well to develop an exercise that has stimulated capability development”

Still, the admitted fuzziness of the loss projections and repeated references to wide error bands does bolster the case of those who think the quantitative focus of climate stress tests is misguided. Says Pekka Piirainen, an associate at UK consultancy Climate Risk Services:

“There is a danger of over-quantification. The long and short of it is there are significant limitations in terms of the data going into the CBES, and though the BoE haven’t said exactly how limited, that’s obviously affecting the output. Hence all the talk about the huge magnitude of uncertainty in the results. It may be best for climate stress testing to move away from overly quantifying complexity, and to take a scenario planning approach instead that is transparent about the fundamental limitations of what can be known, given the challenges”

Putting the data, modeling, and uncertainty factors aside, other aspects of the results challenge the idea that the climate shocks projected by the CBES would be “bearable.” For starters, in some cases a large portion of projected losses crystalized over a short time period. For example, under the LA 40% of losses — around £44 billion worth — occurred over the first five years of the transition. This amount of financial carnage unleashed over a tight time frame could certainly render some institutions temporarily more vulnerable to additional shocks, the combination of which could be enough to put them in distress.

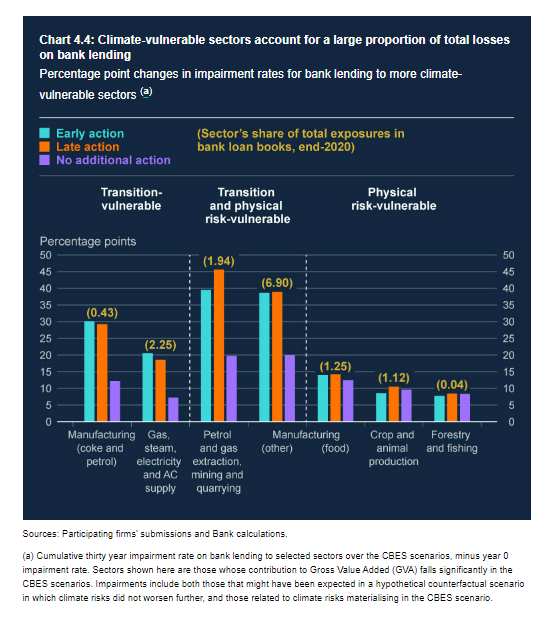

The sectoral concentration of projected losses was also eyebrow-raising. Under the transition risk scenarios, business loans representing 14% of banks’ total corporate exposures were projected to produce about one-third of their overall credit loss provisions. Loss rates for those loan portfolios vulnerable to both physical and transition risks were also far higher than those menaced by one or the other alone. For example, cumulative 30-year impairment rates for bank loans to petrol and gas extraction, mining and quarrying increased around 40% under the EA, 45% under the LA, and 20% under the NAA. This illustrates how overlapping and cascading climate risks are those most likely to play havoc with banks’ capital planning.

In terms of physical risk, the CBES revealed that these too are concentrated — but geographically rather than sectorally. Almost half of total projected mortgage losses stemmed from just 10% of postcode districts under the NAA, reflecting banks’ estimates of those areas most threatened by rising flood risks. As with the rest of the results, the BoE cautioned that these figures may be way off the mark because of data gaps and modeling assumptions.

Though they grabbed the headlines, these loss projections weren’t the only outputs from the CBES. The BoE also shared firms’ planned actions in response to transition and physical risks, helping to remedy somewhat the shortcomings of the ‘static balance sheet’ approach. Under the EA and LA, banks said they intended to curb lending to carbon-intensive sectors and extend balance sheet to the gas and electricity supply sector, especially to renewable energy firms. Significantly, firms explained to the BoE that their borrowers’ transition plans would inform their decision making, underlining the importance of this emerging field of disclosure to the future allocation of bank capital.

Also notable was how the BoE highlighted second-order risks linked to banks’ planned actions, which could compound the losses projected under the scenarios themselves. For example, the Bank noted how the planned withdrawal of credit from the fossil fuel industry “could outpace the new investment in sustainable energy alternatives and improvements in energy efficiency”, an imbalance that could “have significant impacts on businesses and consumers, and through them the financial sector.” Even more intriguing, the BoE cited the risks of herd behavior by banks in relation to their transition responses, saying the “collective impact” of their respective plans “could have negative consequences for the wider economy,” for instance by sparking a vicious cycle of divestment and asset devaluation. Fears that banks could all stampede in the same direction in response to external shocks have been raised by regulators in the context of other risks, especially market risks. There may be significant implications for banks’ own transition planning if the BoE further investigates the ramifications of herd behavior in this context.

What of the immediate policy implications of the CBES results? Sam Woods offered a brief sketch of these in his Tuesday speech. Perhaps the most important takeaway was that the BoE is not closing its door to changing the capital framework to better capture climate risks. Sure, Woods said the results do not make a clear case, in his view, for “a fundamental calibration of capital requirements for the system.” But he went on to say that because climate change “makes the distribution of future shocks nastier” this could “imply higher capital requirements, all else equal.” He also suggested that banks need the “right incentives” to build up their climate risk management capabilities. One such incentive could be provided through the Pillar 2 capital framework, which the BoE could use to introduce capital add-ons for lenders that don’t appropriately measure, monitor, and manage their climate risks.

Beyond informing capital requirements, the BoE intends the CBES results to serve as a health check of banks’ existing climate risk management. Significantly, the institution-level results are being used by the BoE to judge banks’ alignment with its supervisory expectations, which cover climate governance, risk management, and disclosure. Using scenario analysis this way is the ‘safe’ choice for the supervisor, since it need not presage a broader overhaul of the bank regulatory framework or a public airing of banks’ climate risk deficiencies. But it also means that the full consequences of the CBES, at the institution-level, will be kept out of sight, since the BoE intends to engage each participant one-on-one.

There’s plenty more to be said about the CBES, but it will be months before the dust settles and the implications of the exercise come into sharper focus. A deeper understanding of the findings also depends on the participants’ willingness to share their individual results with the public, which they may choose to do so in forthcoming climate-related financial disclosures. Climate risk aficionados and activists alike should push for this degree of transparency to ensure the full value of the CBES is unlocked.