European financial authorities are talking up the potential of the systemic risk buffer to capture physical and transition risks, but the tool has its shortcomings

Bank regulators must be fond of capital buffers. Otherwise they wouldn’t have so many in their rulebooks. In Basel III — the incoming global regulatory framework defined by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) — there’s a capital conservation buffer, a countercyclical capital buffer, a global systemically important bank buffer, and a total loss-absorbing capacity buffer. Most jurisdictions that subscribe to BCBS rules have their own menagerie of buffers, too. Small wonder, then, that regulators are now exploring how these buffers could be used to tackle climate-related financial risks.

Capital buffers are a little different from minimum capital requirements. If breached, minimum requirements signal a bank is in serious trouble. Usually at this point the bank’s supervisor will step in and demand that it take strong actions to conserve capital, cut risk, and reduce leverage. Buffers sit above these minimum requirements, serving as an additional loss-absorbing resource for banks. Some behave as early warning indicators, alerting regulators and shareholders if and when a bank is nearing its minimum requirement. Others serve as a safety valve, forcing banks to build up capital in good times so that they have an extra reserve in bad times.

Still others act as enhanced safeguards for the financial system as a whole. This is true in the case of the global systemically important bank (G-SIB) buffer, which applies only to the largest and most interconnected banks. The reasoning goes that these goliaths should have to hold more capital than their smaller brethren, because if one of them imploded the shockwaves would disrupt the entire network of financial institutions. Put another way, the G-SIB buffer forces big banks to internalize the potential costs they could inflict on the world by virtue of their size.

A macroprudential buffer like this also looks attractive to some regulators as a means to harden the financial system to climate risks. In recent weeks, a troupe of European financial agencies have published their thoughts on the European Commission’s latest update to the bloc’s banking rules, as well as a broader call for advice on the state of the macroprudential framework. All of them talk of using the EU’s existing systemic risk buffer (SyRB) to address climate risks.

The SyRB is a capital tool that allows EU member state authorities to impose additional capital buffers on all or some of their supervised institutions. These buffers can apply across whole portfolios, or just specific subsets deemed to be particularly threatening to financial stability.

A scan of the European Systemic Risk Board’s website shows that SyRBs today are used to guard against all kinds of risks. For example, the Bank of Lithuania set an SyRB in March for 21 large institutions, which added a 2% buffer to these banks’ exposures to residential mortgages. The Bank justified the buffer as a response to “macroprudential risk stemming from the increased concentration of the banking sector’s exposure to mortgage loans.”

Elsewhere, Finansinspektionen — Sweden’s regulator — has since 2014 applied a portfolio-wide SyRB of 3% on the country’s three largest financial groups because of their closely related business models and the concentration of financial assets in their hands.

By nature, the SyRB gives national authorities broad latitude to set buffer requirements. For some, this design feature makes the SyRB well-suited to capturing climate risks. As the European Central Bank (ECB) wrote in an opinion paper to the European Commission, “the flexibility embedded in the provisions of the systemic risk buffer” allow it to address “different types of systemic risk, including climate risks.” It went on to say that the incoming EU capital framework should state that the SyRB could apply to subsets of exposures particularly “subject to physical and transition risks related to climate change.”

The European Banking Authority (EBA) is of a similar mind. In a recent paper, it too extolled the benefits of the SyRB, and in particular how it can be stretched or shrunk to cover all kinds of exposures. The EBA even suggested certain tweaks to existing rules that could make it more effective against climate risks.

First, it recommended a “classification system” be set up to pinpoint those sectors or sub-sectors linked with climate-harming activities. This is so a climate SyRB could be applied uniformly across bank portfolios and member states. This may not prove too difficult. After all, the EU’s sustainable taxonomy already identifies climate-friendly activities, and certain policymakers and think tanks are calling for a corresponding ‘dirty’ taxonomy for polluting activities. Even in the absence of a ‘dirty’ taxonomy, though, a classification system for the SyRB could be defined using those activities not covered by the sustainable taxonomy.

Second, it said the SyRB should be expanded so it can be applied to banks’ cross-border assets. Right now, the rules limit its application to domestic exposures only. Without a change, a climate SyRB would only be able to capitalize a bank’s home country climate-vulnerable exposures while leaving similarly at-risk assets overseas untouched.

How difficult it would be for EU lawmakers to make these changes remains to be seen. But even if they could make them, should they? Is the SyRB the right macroprudential tool to shield banks from climate risks — particularly transition risks?

There are a number of reasons to doubt that it is.

Yes, financial authorities concerned about stranded asset risks could impose an SyRB on banks’ fossil fuel exposures, at the sector or sub-sector level. However, this discretion also empowers authorities to pick winners and losers. One could do so by applying a sectoral climate SyRB on some carbon-intensive sectors (or banks) but not others. For example, an EU member state that does not have a lot of coal in its energy mix may have no qualms about imposing an SyRB on its banks’ exposures to this fossil fuel. But another that is heavily reliant on coal may shy away from taking similar action.

The ECB, in a response to Climate Risk Review on this question, implied that the structure of the SyRB should prevent this kind of misuse:

“The SyRB has been actively used over recent years to address excessive risk to the financial system from a structural perspective. The SyRBs sectoral use for climate should thus not be seen as picking winners and losers but as a policy reaction to the build-up of structural system wide risks…Already now there are procedural criteria in place that need to be fulfilled when a Member State decides to use a sectoral SyRB (e.g. it needs to inform the ESRB). However, no applications for climate risk have been submitted yet and it is possible that some amendments will be needed.”

Here’s a second problem: the SyRB is not calibrated to the actual risk profile of transition risk-sensitive assets. While it is true that the low-carbon transition will occur at different speeds in different regions of the world, the end-state should be the same everywhere: the elimination of coal-fired power, a massive reduction in oil and gas power, and the transformation of all carbon-intensive industries. If stranded asset risk is universal, it makes little sense to guard against it in a patchwork fashion — with some member states imposing a high SyRB on some sectors, and others a low one, or none at all. When it comes to physical climate risks, however, a more tailored approach may be justified considering the geographic dispersion of these threats.

A third problem is that the SyRB’s firepower is limited. Yes, authorities can set an SyRB at whatever rate they choose. But if the combination of the SyRB and two other EU buffer rates — the other systemically important institution (O-SII) and global systemically important institution (G-SII) buffers — exceeds 5%, then the European Commission has to explicitly authorize the increase.

Furthermore, under current rules no distinction is made between SyRB rates imposed on all exposures and SyRB rates imposed on just some exposures in the context of the 5% threshold. This means an EU authority could set a high SyRB rate for a tiny fraction of its supervisees’ portfolios and trigger the authorization requirement.

It’s possible these rules may be having a chilling effect on the application of SyRBs across the bloc. The EBA certainly thinks so, having written that the threshold “impedes the use of the sectoral SyRB, especially for smaller exposures that have an elevated risk and require relatively high buffer rates to increase the capital requirements notably.”

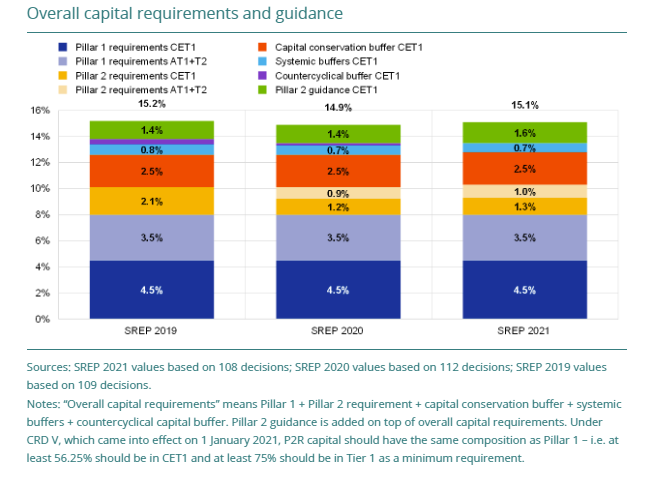

Indeed, this chilling effect may be one reason why prevailing systemic buffer rates are so low across the EU. ECB data shows that in 2021, systemic buffers (the SyRB plus O-SII and G-SII) made up just 0.7 percentage points of banks’ overall capital requirements and guidance. This is far lower than the 1.3 percentage points attributable to required Pillar 2 capital requirements, another add-on set at the discretion of national authorities.

Source: ECB

In order to address transition risks effectively, regulators would have to be able to set a climate SyRB at a high level without constraints to ensure banks have sufficient capital to withstand a sharp drop in the value of their fossil fuel assets.

The ability to set a high SyRB is also important if the EU chooses to adopt a ‘precautionary approach’ to climate regulation, whereby capital requirements are set with the objective of deterring banks from funding activities that will push the world beyond the crucial 1.5°C warming threshold. Only a high enough sectoral SyRB that makes financing new fossils prohibitively capital intensive would get the job done.

The existing limitations of the SyRB, then, arguably make it ill-suited to addressing bank climate risks. So why is it being floated by EU agencies as a useful tool? One reason may be the challenges inherent in changing microprudential capital rules. These are the Pillar 1 minimum capital requirements and Pillar 2 supervisor add-ons that are tailored to each bank’s own risks. Rewriting all these rules to incorporate climate risk would be a massive challenge, and may rest on shaky empirical grounds — as the EBA itself argued in a recent discussion paper. In contrast, giving individual member state authorities the option, but not the obligation, to incorporate climate risks into SyRB add-ons should be far simpler.

Yet without changes to microprudential rules, undercapitalized climate risks could still bubble up within individual banks. True, the ECB is working to incorporate climate risk into the annual review process it uses to set Pillar 2 requirements. The ECB also told Climate Risk Review that macroprudential and microprudential supervisory approaches “may need to complement each other … to account for the long horizon of climate-related risks and the complex way they interact.”

Still, absent a comprehensive effort to factor climate risks into all microprudential rules, especially those governing Pillar 1 capital minimums, EU policymakers are taking a gamble with the safety and soundness of their financial institutions. Trusting in a nebulous buffer framework to do the hard work for them simply kicks the can down the road.