A new study by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association suggests market risk rules unfairly penalize carbon trading

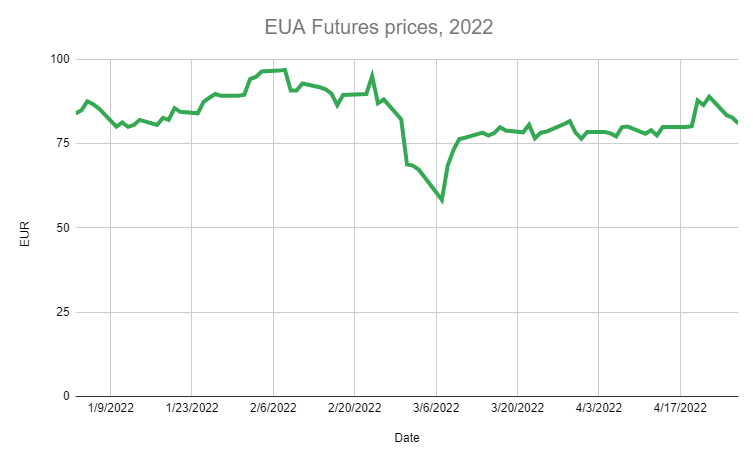

Carbon markets yo-yoed dramatically in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Futures on European Union Allowances (EUA), the derivatives contracts that facilitate the trading of greenhouse gas emissions in the EU, tumbled 29% from February 28 to March 7, before surging 32% over the subsequent four days. The turmoil shined a light on the volatility of carbon markets, and the risks to financial and non-financial entities of trading in carbon credits.

Source: Ember

In the banking world, capital buffers are used to protect against trading risks, and regulators set minimum capital requirements to ensure that banks size these buffers appropriately. But sometimes (or a lot of the time, depending on who you ask) financial watchdogs set capital requirements that are misaligned with these trading risks. In doing so, they tie up resources that banks could otherwise deploy making markets and servicing clients.

The International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA), a trade body for buyers and sellers of derivatives, believes regulators are making just this kind of mistake when it comes to carbon credits — which could hinder the emissions markets many jurisdictions are relying on to drive the energy transition, not to mention the nascent voluntary carbon offset markets financial institutions are working to develop.

Here’s how Gregg Jones, Senior Director, Risk and Capital at ISDA, explained the problem to Climate Risk Review:

“Why are banks concerned? Emissions trading schemes will play a part in tackling climate change. Ultimately, we want to make sure banks are able to facilitate for clients that are part of those schemes, but if capital charges are too punitive relative to the underlying risk of the actual product, then that obviously doesn’t provide the right incentives. Punitive capital charges could require banks to make a business decision about whether they are able to participate in that market moving forward”

To show how incoming capital requirements for carbon trading are inappropriately sized — at least from its perspective — ISDA released an analysis last week of the risks to banks of acting as market makers in three carbon markets — the Western Climate Initiative (WCI) and Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) in the US, and the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) in the UK. This paper follows a similar study that ISDA published last July on the trading risks linked to the EUA futures market, which Climate Risk Review discussed at the time.

The latest analysis reaffirms ISDA’s earlier assessment that the capital treatment of carbon credits under the Fundamental Review of the Trading Book (FRTB) — part of new global banking rules known as Basel III — is out of sync with the historical volatility of these instruments. Put another way, the rules would force banks to hold more capital against their carbon credit positions than can be justified by their worst-case performance.

Using historical data for the WCI, RGGI, and UK ETS, ISDA calculated the stressed period of volatility for futures in these markets to be 33%, 20%, and 44%, respectively. These are all lower than the volatility of EUA futures, which ISDA pegged at 56% in its analysis last year. ISDA said these volatilities correspond with a risk weighting of 13% for WCI futures, 22% for RGGI futures, and 37% for EUA futures. Risk weights are applied to trading positions under Basel III to calculate their minimum capital requirements. The higher the risk weight, the higher the resulting capital charge for a given position.

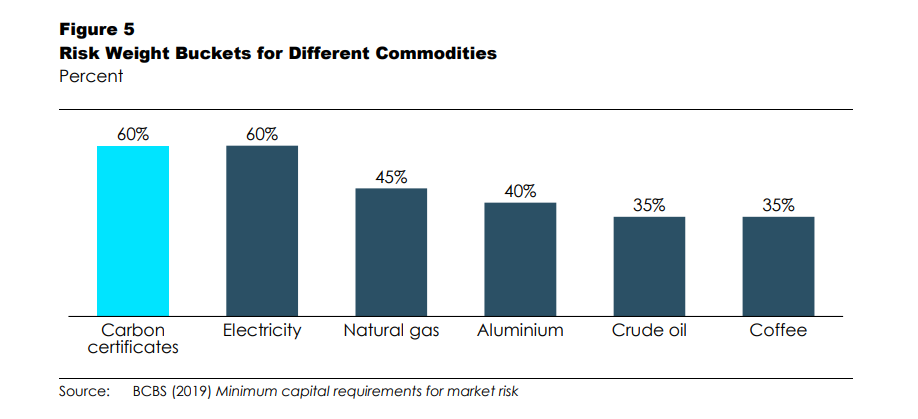

The FRTB has assigned all carbon credits a flat 60% risk weight under its standardized approach (the approach many banks will be using), which is the same as that applied to electricity contracts — a famously volatile commodity. Based on the EUA futures historical volatility, ISDA recommends a risk weight of 37% instead of the 60% applied by the FRTB.

Source: ISDA

Of course, this recommendation hinges on the dataset scrutinized by ISDA. The association’s initial study of EUA futures prices screened out the highly volatile 2008-2012 period on the grounds that the market’s behavior then was the result of “flaws in the design of the scheme” — flaws it says have since been remedied by the EU’s increased political commitment to the ETS. ISDA says the 2008-2012 period is unrepresentative of the market today and therefore that it makes sense to be excluded from its data analysis.

This time around, ISDA has to contend with the fact that its dataset does not include the highly volatile period kicked off by the Russia-Ukraine war. However, Jones insists that this does not undermine the paper’s conclusion:

“We sourced the data for this second study prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but we ran a sanity check using data covering the recent volatility. One of the interesting points is that the actual relative shock to the EU ETS was still not as big as 2016-2018 because the price was a lot lower at that particular time. So the relative size of the shocks was smaller, even though the absolute size was a lot larger”

Put simply, a 37% risk weight is appropriate in ISDA’s assessment even given the latest whipsaw in EUA futures prices.

The ISDA paper also argues that the FRTB’s assumptions about the correlation of carbon instruments of the same type but of different maturity are flawed. This alleged flaw in the rules would penalize banks that run ‘carry positions’ — where they buy daily/one-month futures (depending on the market) and sell end-of-year futures. Running carry positions is part and parcel of being an intermediary in any commodities market.

ISDA says there is a higher correlation between near-dated and far-dated carbon futures than implied by the FRTB. If this were reflected in the capital rules, the charge for a typical carry position would fall by 40%. Taken together, ISDA’s recommended changes to carbon credits’ risk weighting and correlation factor would result in a whopping 60% reduction in capital requirements.

Put another way, ISDA’s findings imply that under FRTB banks will be overcharged for running carbon credit trading books. This could deter some institutions from getting involved in carbon markets in the first place, and push some existing participants to scale down their activities. This in turn could reduce the liquidity of carbon markets, making trading the instruments more expensive for end users. Alternatively, it could entice ‘shadow banks’ into these markets — less regulated financial institutions with thinner capital buffers than traditional lenders. Such firms could introduce new risks to carbon markets, especially if they ran into liquidity or solvency issues.

The involvement of non-bank financial entities in the EUA futures market is top of mind at the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), one of the European Union’s major financial watchdogs. In a recent report on the functioning of the bloc’s carbon market, ESMA noted that “the number of investment funds taking part in the market is high” and that the share of trading activity by non-EU entities reflects “to some extent the presence of algorithmic trading as well as high-frequency trading,” both of which show that non-banks are becoming increasingly important to the market’s operation.

Right now, ESMA says these entities’ involvement is no cause for concern, given the small positions they take relative to other participants. Still, their involvement is a trend worth monitoring. The report cites academic research which underlines “the growing number of speculative positions both from financial and commercial traders,” which may have an impact on the market’s volatility.

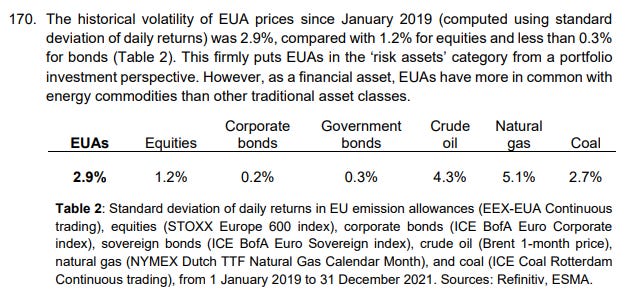

Other aspects of the ESMA report indirectly push back on the narrative offered by the ISDA paper. For example, the report includes ESMA’s own analysis of EUA futures’ price volatility, which concludes that the products “have more in common with energy commodities than other traditional asset classes.” This would seem to reinforce FRTB’s decision to assign carbon credits the same risk weight as electricity.

Source: ESMA

Because ESMA and ISDA use different measures of volatility to arrive at their conclusions, it’s hard to refute their respective conclusions on the nature of carbon markets. What matters most for banks, though, is what volatility narrative makes most sense to the lawmakers currently transposing FRTB into binding regulation.

In the EU, Basel III is being embedded into the bloc’s revised Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR). Last October, the European Commission proposed that the risk weight for carbon credits be set at 40% — much closer to ISDA’s 37% than the FRTB’s 60%. Furthermore, the Commission said equating carbon trading to electricity trading “could be considered too conservative in light of historical data relevant to the EU market for emission allowances” and that the volatility of the carbon market has stabilized in recent years thanks to political fixes — something ISDA also believes.

The European Parliament and Council are currently reviewing the Commission’s proposal as part of the standard legislative process, and may recommend the 60% risk weight be reinstated. Interestingly, the European Central Bank has spoken out in favor of the EU staying true to the original Basel III rules, stating in a recent opinion that the framework should be faithfully implemented so that capital requirements are applied consistently at the international level.

What is eventually decided at the European level could have ramifications for how the FRTB is applied in other jurisdictions. If the EU adopts a lower risk weight for carbon credits, other regions may follow. Such a decision could cement banks’ place in the carbon trading system and help carbon markets to flourish.

However, it could also store up trouble for the future — particularly if the carbon markets become more volatile as the Russia-Ukraine war drags on and mooted changes to the functioning of markets in the EU and US go ahead.