The umbrella group of climate finance alliances has rolled out what could be a game changing new framework on transition plans

Yesterday marked what could be a decisive turning point in the effort to marshal financial institutions in support of net-zero emissions goals.

First, the UN-backed ‘Race to Zero’ (RtZ) campaign — an over 10,000 strong coalition of businesses, financial institutions, and government bodies — updated its criteria for membership. Now, all new members are explicitly required to “phase down and out all unabated fossil fuels as part of a just transition.” Existing members have until June 15 next year to honor this new commitment.

This has major consequences for the more than 500 banks, insurers, asset managers, and asset owners that are part of the RtZ campaign through their membership of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) — the umbrella organization for financial institutions committed to accelerating the transition to a net-zero economy. Why? Because the RtZ requirement means they “must restrict the development, financing, and facilitation of new fossil fuel assets.”

Prior to this change, GFANZ members were not bound by any explicit requirement to choke off their financing of oil, gas, and coal. Now they are. Failing to meet this requirement could expose an institution to reputational risk, and in future may even force them to leave the alliance.

Second, GFANZ itself released a bundle of new advice and recommendations for its members, including a comprehensive framework on how financial institutions can develop and implement net-zero transition plans (NZTP), which is open for public consultation until July 27. This guide should help GFANZ members honor another of the RtZ campaign’s new requirements: that they publicly disclose a transition plan within 12 months. Climate Risk Review spoke with two GFANZ executives on the guide. An edited transcript of the discussion is at the end of this article.

The RtZ criteria update and NZTP framework show that GFANZ is evolving from a paper tiger into a climate alliance with real teeth. Just a few months ago, the group was stung by criticism that it was greenwashing financial institutions, and embarrassed by reports that it had tried and failed to get banks to commit to a portfolio decarbonization pathway that would have barred the financing of new fossil fuel projects. Now, it has the tools in hand to steer members away from oil, gas, and coal, and toward the low-carbon future.

The NZTP framework has a lofty goal: to help financial institutions demonstrate, and stakeholders to judge, the credibility of their plans to ramp up clean energy and “transition-related finance” in line with a 1.5°C warming limit. This focus on credibility is significant, since plenty of financial institutions have rolled out transition plans only to have them attacked by investors and climate activists as so much greenwash. UK banks Barclays and Standard Chartered and Switzerland’s Credit Suisse are three recent examples. Firms that adhere to the NZTP framework may be able to avoid similar embarrassments.

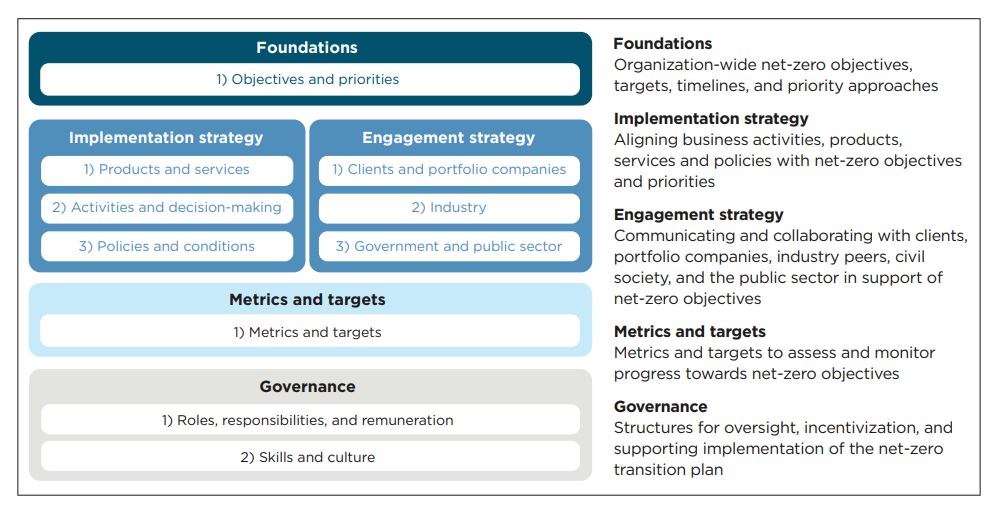

The framework is organized into ten core components, which are grouped into five themes: Foundations, Implementation strategy, Engagement strategy, Metrics and targets, and Governance. GFANZ says financial institutions that follow the components should be able to put together transition plans that are “actionable, focused on near-term action, and aligned with a carbon budget for limiting warming to 1.5 degrees C.”

Source: GFANZ

Besides the practicalities of putting together credible transition plans, the framework also touches on the interplay between transition planning and climate-related financial risk management — concepts which exist in mutual states of synergy and tension.

Put simply, climate-related risk management is about integrating climate change into a financial institution’s risk governance, policies, and practices. It’s focused on guarding the institution from financial losses linked to climate impacts. Transition planning, in contrast, is about aligning the strategy of a financial institution with global net-zero goals. In practice, it’s focused on directing finance toward low-carbon and climate-friendly activities.

These two goals may not always be compatible with one another. GFANZ even says a transition plan should “look beyond an institution’s own risk profile” to support the real economy’s journey to net zero. In other words, it should be outward-looking, not inward-looking. This directive may lead to trade-offs between the climate finance and risk management functions at financial institutions as the global transition advances.

Much depends on the scope of a firm’s climate risk management. If it is narrowly defined, conflicts may be frequent and messy. For example, an institution’s risk function may want to dump investments in fossil fuel companies to reduce its stranded asset risk. However, doing so could conflict with its NZTP, which may demand ongoing engagement with such companies.

At the other end of the spectrum, a firm with a broad conception of climate risk, which respects that it is both systemic and exogenous, could avoid such fights. GFANZ itself argues that climate risk management and NZTPs can be “mutually supportive.”

How banks, insurers, and other firms balance the demands of climate risk management and transition planning remains to be seen. Get it wrong, though, and both financial stability and the economy-wide net-zero transition could be imperiled.

Climate Risk Review spoke with GFANZ’s Joy Williams, Executive Director, Financial Institution Transition Planning, and Tony Rooke, Executive Director, Climate Transition Planning and Sectoral Pathways about the NZTP guide and framework.

What follows is an edited transcript of the conversation:

Climate Risk Review (CRR): How will GFANZ work to get signatories to adopt the NZTP guidance?

Joy Williams:

“Each of the net-zero alliances as part of GFANZ is responsible for setting their own criteria in partnership with the UN Race to Zero — GFANZ does not set criteria. What our focus has been is to produce helpful, pan-sector, globally applicable guidance. We are providing that common framework, that common language, for net-zero transition plans. It’s there for all members to make use of in whatever way they find helpful. But it’s also there to provide external stakeholders, like regulators, a common framework for the financial sector. We work very closely with the net zero alliances, and they have been involved with everything that we do right from the start.”

CRR: How does the NZTP guidance incorporate or complement other net-zero transition frameworks that are out there, like the SBTi and the UK Transition Plan Taskforce?

Tony Rooke:

“Our main objective is to synthesize and amplify what’s already out there so that we get consistency on transition planning. We have referenced the SBTi specifically, and the work they’ve been doing, as well as others including the Transition Pathway Initiative, the TCFD, ACT, CA100+ and CDP. We’re also engaging with regulators and standard bodies, such as the ISSB, so that everybody gets the same picture and moves in the same direction.”

Joy:

“We’re drawing on the best practice today in the industry to inform a pan-sector approach. We believe that it is quite complementary to other groups. But this NZTP report is really centered around action. It’s meant to be a strategic planning tool which financial institutions can implement, so it’s more than just a guide to setting targets. It’s focused on involving different financing teams, different business functions. That’s what we’re addressing — how do you steer the ship in a different direction?”

CRR: None of the “four essential approaches for financial institutions to support the real-economy transition to net-zero emissions” explicitly reference removing financing from high-emitting activities/sectors. Why is that?

Joy: “The way we developed these approaches goes back to our definition of what a net-transition means to finance. There’s two foundational concepts to that. One is that it is an action plan — it’s something they do. Two, it’s focused on emission reductions in the real economy. We don’t want this to be ‘on-paper’ decarbonization, it has to actually result in real-economy emissions reductions. When we thought about that, we asked ourselves what does finance do? Finance moves capital to where it’s needed. In the context of net zero, those four approaches are about where financing is actually needed. We have to develop and scale climate solutions, we have to continue to support companies who are already on the pathway, we have to get companies who are not on the pathway — both high- and low-emitting — to develop transition plans, and then start to implement those transition plans, and finally, we need early retirement of the high-emitting physical assets that cannot transition to net zero.”

CRR: The NZTP guidance makes a distinction between transition planning and climate-related risk management. It says that transition plans “look beyond an institution’s own risk profile.” How do you reconcile transition planning with climate risk management in this guidance?”

Joy:

“Risk management — the identification of climate risks, understanding what they mean for your own business activities — we feel that leads naturally to the question: what are you doing about the risks? That’s where the transition planning is coming in. There’s a feedback loop — once you start doing the transition, and the financial sector as a whole starts to transition, that should feed into your risk identification and assessment. Also, it is likely that transition planning and climate risk management will involve different groups within an institution because they are different activities.”

Tony:

“There’s a recognition from many of the financial institutions that net zero planning is partly there because the long-term risk from business-as-usual means that the economy itself faces a systemic risk that it may not recover from. Financial institutions are incentivized to make the transition happen because of this long-term systemic risk that may not be fully captured in a scenario analysis, simply because the models aren’t good enough yet.”

“If you took a traditional portfolio decarbonization approach, you may say: ‘I have invested in this energy company, but these two tech firms look like much lower emissions risk, so I should switch to them to decarbonize’. If you do that, that may reduce your financed emissions, but you’re not actually reducing your secondary or tertiary risks from the systemic risk, because the energy company will potentially go somewhere else and do business as usual.”

“Also, of the two tech firms, one may focus on energy efficiency, which could help with net zero, and the other one could be providing software that helps companies exploit more fossil fuels — which then drives climate risk! So just using the emissions profile of a particular company doesn’t necessarily reduce your systemic risk, whereas financing the transition, will actually bring about decarbonization in the real economy, which then systematically brings down the physical risk to all of us from climate change.”