Regulators are pushing ahead with mandatory climate-related disclosure requirements, but how can they ensure banks’ reports aren’t full of ‘white noise’?

There’s no denying it — banks’ climate-related disclosures are getting bigger. But are they getting better? The European Central Bank’s (ECB) latest stocktake on the substance and quality of such disclosures suggests not.

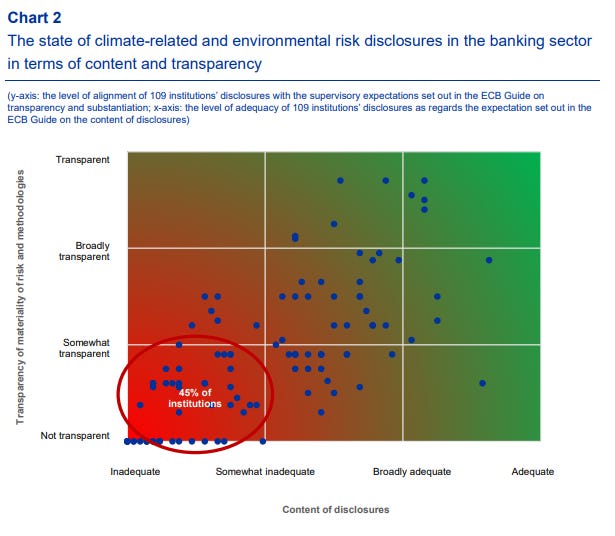

The exercise, which assessed the alignment of 109 banks’ most recent public filings with the ECB’s supervisory expectations on climate-related and environmental (C&E) risk management and disclosure, found that although a larger percentage of institutions are including C&E indicators in their reports, most still aren’t relaying key information. Nor are the majority being transparent about the materiality of their C&E risks and methodologies.

Significantly, the exercise also revealed that while half of the banks assessed produced indicators linked to C&E risks, many of these related to “green financing” rather than risks per se. Findings like this explain why Frank Elderson, Vice-Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, said: “Banks are trying to compensate for the poor quality of their disclosures by issuing a great volume of information around green topics”, which is leading to “a lot of white noise and no real substance on what both markets and supervisors really want to know: how exposed is a bank to C&E risks and what is it doing to manage that exposure?”

A “flood the zone” approach to climate-related disclosure makes sense for banks that want to relieve pressure from investors and supervisors without actually grappling with their climate risks. However, it’s only an option in the absence of clear disclosure standards that are actively enforced by relevant authorities. That’s why the European Banking Authority’s (EBA) Pillar 3 standards on the disclosure of ESG risks are so important, as they would mandate the disclosure of specific indicators and standardize their presentation. Though these standards have gaps and do not prescribe what approaches banks should take to fill in certain indicators — both factors that may diminish their usefulness to bank investors and regulators — they would at least compel banks to issue clear signals amid the white noise.

A desire for more clarity and less filler also animates the proposed rule on climate-related disclosure published by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on Monday. In its rationale for the proposal, the SEC says it is “concerned that the existing voluntary disclosures of climate-related risks do not adequately protect investors”, noting that the current grab bag of reporting approaches “makes it difficult to assess how much material climate-related information firms currently are disclosing and may leave opportunities for companies to omit unfavorable information.”

While the SEC doesn’t go as far as the EBA in proposing standardized disclosure templates in its rule, it is fairly prescriptive about how specific datapoints should be presented. For example, Scope 1 and 2 emissions are to be reported in absolute terms disaggregated by constituent greenhouse gas and in the aggregate in CO2-equivalent amounts, consistent with the methodology used by the GHG Protocol. They also have to be disclosed in intensity terms — specifically, metric tons of CO2e per unit of total revenue and per unit of production. To ensure companies report these figures in a transparent manner, the proposed rule also says they must “describe the methodology, significant inputs, and significant assumptions” used for these calculations.

This prescriptiveness extends to physical and transition risks, too. Under the proposal, firms would have to report the financial impacts of extreme weather events, other natural conditions, transition activities, and other identified climate-related risks on their revenue, cost of revenue, selling, long-term debt and more if the aggregated impacts exceed 1% of the total line item for the relevant reporting period. Because the financial performance of banks is indelibly linked to the financial performance of their borrowers, it’s likely that many lenders — particularly those with concentrated exposures to fossil fuel industries and/or regions susceptible to climate-related flooding, storm surge, and wildfires — would trigger this reporting threshold.

However, one gap concerns how forward-looking assessment approaches should be described and disclosed. For banks, these typically take the form of portfolio alignment tools, which express a group of investments’ contribution to climate change through a temperature score.

As written, the proposed rule would force companies that have adopted climate transition plans to describe these in their periodic reports, “including the relevant metrics and targets used to identify and manage any physical and transition risks.” It would also require them to “disclose relevant data” to show whether or not they are making progress toward fulfilling their transition goals. This dovetails with the commitments made by members of the Net Zero Banking Alliance, which pledge to annually report “progress against absolute emissions and/or emissions intensity targets following relevant international and national GHG emissions reporting protocols and/or climate portfolio alignment methodologies.”

What’s not clear from the proposed rule, at least on a first reading, is what — if any — disclosures have to be made about these “relevant metrics and targets” and “relevant data.” This suggests that banks could use black box “climate portfolio alignment methodologies” to accompany their transition plans without having to describe how they work. The result could be more white noise, not less.

Prescribing this level of disclosure may be too much to ask of a securities regulator that has to make sure its rules work for all kinds of companies, not just banks. That’s why investor and civil society-led disclosure initiatives tailored to the financial sector are so important — and will stay important even in the coming era of mandatory climate disclosure.

When it comes to the specific issue of banks’ forward-looking assessment approaches, bright minds have already got to work. Earlier this month, the WWF released guidance for financial authorities on standardizing disclosure formats for banks’ and insurers’ climate-related metrics. This included example reporting templates that, if adopted, could lead to greater understanding of how these metrics work and the assumptions and scenarios that inform them. They would also make such metrics comparable across firms, and strengthen disclosure users’ confidence in the outputs they produce.

The world has moved from the era of voluntary climate reporting to the age of mandatory climate-related disclosure. But this does not on its own guarantee that investors, supervisors, and other stakeholders will get clearer signals from companies — and especially financial institutions — on their climate risks and opportunities. Without a continuous effort to promote standardized reporting of what underpins the metrics that banks and other financial firms use to populate their transition plans and climate disclosures, the problem of white noise will persist.