Increasing numbers of banks are reporting data aligned with the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials standard

Climate data aficionados had much to celebrate in the latest round of disclosures from major banks. Annual climate-related reports from Wall Street lenders to rural credit unions came packed with information on their climate risks, opportunities, and transition plans. For the first time, many banks also disclosed their ‘financed emissions’ (FE) — those produced by the companies they lend to and invest in.

This outburst of transparency is thanks in large part to the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF), a financial industry-led group committed to harmonizing the assessment and disclosure of those emissions generated through institutions’ loans and investment. Founded in 2015 by a small band of Dutch banks, PCAF now boasts 232 institutions representing $63.6 trillion in assets, including major lenders Citi, Bank of America, Barclays and TD Bank. Signatories commit to measure and disclose FE within three years of joining using collectively developed accounting methodologies. PCAF released the first iteration of its FE disclosure standard in November 2020.

Though not all members have yet to publish PCAF-aligned disclosures, there are enough in the public domain now to run a preliminary analysis of the state of emissions accounting in the banking sector.

Climate Risk Review analyzed the PCAF-aligned disclosures of 20 commercial banks. On PCAF’s website, there are links to such disclosures from 37 such entities, of various level of maturity. The following takeaways are informed by these 20 banks’ disclosures (the full list is at the end of the article).

The first key takeaway concerns the scope of disclosed FE. Certain banks have produced detailed reports on the emissions linked to most, if not all, of their financing activities, while others have limited their disclosure to a few select portfolios.

UK lender NatWest provides one of the most comprehensive and granular breakdowns of its FE among big banks, with a table containing details for 13 portfolios (some further broken down by GHG emissions scope) covering 52.3% of its total on-balance sheet gross lending and investment exposure.

However, this is nothing compared to the efforts of some smaller lenders. Triodos Bank, one of the Dutch banks that adopted PCAF early, has disclosed FE data for 100% of its exposures since 2019.

Other banks, especially larger firms with sprawling international businesses, have taken a narrower approach. HSBC, the UK’s largest bank, disclosed 2019 FE for bits and pieces of two portfolios: oil and gas, and power generation. Together, the assessed exposures amounted to $23.5 billion — just 3.4% of its total wholesale credit, lending and project finance exposures. It wasn’t alone. Canadian lender TD Bank also disclosed FE for its oil and gas and power portfolios only. Its close rival, Scotiabank, reported FE for four portfolios: oil and gas, power and utilities, residential mortgages and agriculture.

Of course, while these carbon-intensive portfolios may make up a small slice of each bank’s overall loan books, they make up a hefty chunk of their overall FE. For example, Scotiabank estimates the four portfolios it has disclosed may account for over two thirds of its total FE. By focusing on their big ‘carbon hogs’ first, such firms are wisely focusing their efforts on where emissions accounting analysis can reap the most benefits.

It’s expected that the scope of FE disclosures will widen as PCAF iterates upon its standard. Right now, the standard encompasses six asset classes: listed equity and corporate bonds, business loans and unlisted equity, project finance, commercial real estate, mortgages, and motor vehicle loans. Disclosure standards for three more asset classes are currently under development, as well as a standard for “facilitated emissions”, which are those generated by financial institutions’ capital markets activities. The finalization of these standards should empower banks — especially larger banks with more complex balance sheets — to calculate and disclose FE for a larger number of portfolios.

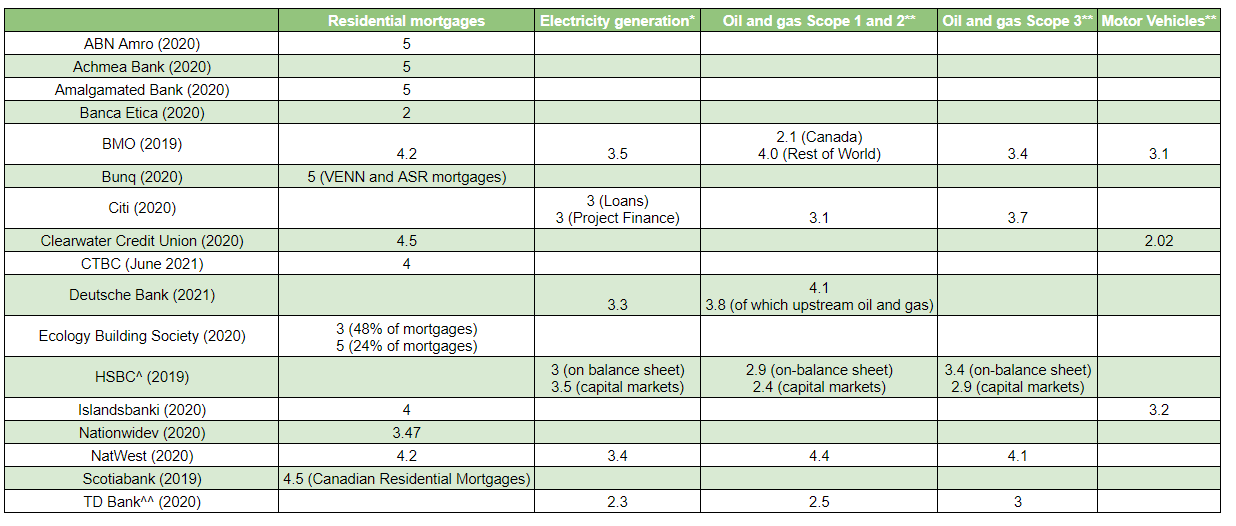

The second takeaway is the low data quality scores assigned to FE disclosures. PCAF cooked up a five-step data quality scoring methodology per asset class — with ‘1’ being the highest and ‘5’ the lowest. Signatories are supposed to report the data quality score for each portfolio they disclose. The idea is that users of the disclosures are then able to get a handle on the accuracy and credibility of an institution’s FE totals. The methodology is also supposed to encourage reporting institutions to improve their data quality over time.

Though the scoring methodology differs by asset class, generally FE disclosures with a ‘1’ score are those which the reporting bank has verified GHG emissions data for in accordance with the GHG Protocol. At the other end of the scale, disclosures with a ‘5’ score are those which a bank has had to use a proxy or estimate to come up with the borrower/investee emissions footprint. This is poor quality data, which may substantially under- or over-estimate a company’s true carbon profile.

Though PCAF itself doesn’t offer indicative ‘error margins’ for the accuracy of emissions data per data quality score in its standard, Triodos Bank says assets with a ‘1’ score have a 5-10% error margin in estimations, and those with a ‘5’ score a whopping 45-50% error margin. TD Bank, meanwhile, offers a 5-10% and 40-50% error margin for these two scores, respectively. This data suggests that users of disclosures should think of low-scoring FE numbers as representing an anchor point in a range of possible values, rather as a definitive value.

Of those bank disclosures analyzed by Climate Risk Review, most assigned data quality scores of 3-5 for the majority of their portfolios. This likely reflects just how few bank counterparties provide verified GHG emissions data. Citi, for example, said that in 2020 just 30% of its power and energy clients reported actual emissions data for Scope 1 and 2, and a tiny 0.1% for Scope 3. Furthermore, only 11% of total data was verified.

PCAF data quality scores for select portfolios, by bank

* BMO ‘Power Generation’, TD ‘Power’, HSBC ‘Power and utilities’, Deutsche Bank ‘Power Generation’, Citi ‘Power’

**BMO ‘upstream oil and gas’, TD ‘Energy’, Citi ‘Energy’

***BMO ‘Motor vehicles (sale and use)

^On-balance sheet financed emissions

^^Total committed lending amounts

Source: PCAF, bank disclosures. Dates refer to reporting year of financed emissions

In the absence of a legal or regulatory duty to disclose, the burden of getting companies to collect and report emissions data is shouldered by financial institutions themselves. Some banks are finding ways to incentivize their borrowers to do so, for example by warning clients that they will be cut off from their services if they fail to provide the information. It remains to be seen whether such efforts will bear fruit, or whether public company disclosure requirements, like those about to be proposed by the US Securities and Exchange Commission, will be what pushes FE data quality scores up.

In the interim, given the low quality of much FE data, institutions may consider publishing their own ‘error margins’ for FE per portfolio alongside the ‘official’ FE amounts. This would help stakeholders understand the level of confidence institutions have in their FE totals, and enhance the credibility of analysis and forward-looking projections based on them.

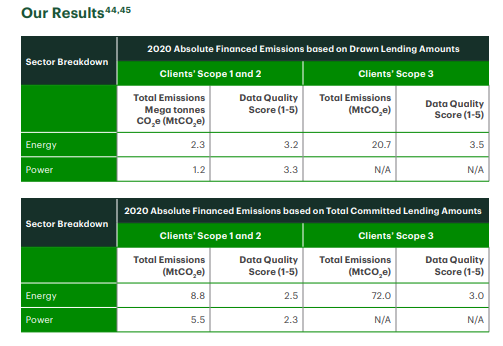

A third takeaway concerns the nature of financing activities captured by the PCAF methodology. Significantly, the PCAF standard tells institutions to calculate the FE of outstanding loan amounts — meaning the credit actually drawn upon by a borrower. This is different from committed amounts, which is the maximum amount of credit a borrower can draw upon. Large banks typically offer revolving credit facilities to corporate borrowers that they can tap as and when they choose over a given time horizon, like a credit card. PCAF says that FE only have to be accounted for when such facilities are utilized.

Some banks disagree. Citi says that using committed funds to establish its FE baseline for its internal net-zero targets “will allow us to better capture how changes in Citi’s lending practices over time alter our exposure to climate risk and can contribute to the net zero transition.” However, it admits that in doing so it is likely to overstate its FE, as it is counting emissions that it could potentially finance as well as those it is activelyfinancing. It also means that there will be discrepancies between the FE numbers reported in its future PCAF-aligned disclosures and for its net-zero target disclosures.

TD Bank, meanwhile, elected to disclose FE amounts for both drawn and undrawn balances. So far, it looks like PCAF’s dream of harmonizing FE disclosure practices is some way from being made a reality.

Source: TD Bank

Other banks besides Citi are adapting or amending the PCAF methodology to better fit their in-house view of how FE should be calculated. Scotiabank, for instance, says it has “identified instances where deviations from the PCAF methodology are justified” in relation to its oil and gas exposures. Specifically, it said the PCAF methodology produces “highly volatile results, unrelated to actual change in emissions” for these exposures because of the “cyclical nature of oil prices resulting in material fluctuations in enterprise value and clients drawing on committed facilities at different times even if underlying client emissions changed very little, or not at all.”

Some PCAF signatories have bypassed the methodology entirely — at least for now. Barclays, a PCAF signatory since November 2020 and Co-Chair of the partnership’s Capital Markets Working Group, has used its own proprietary BlueTrack methodology to measure and disclose FE. In its latest report, the bank said there is “no consistent industry-wide approach to measuring emissions” but that it is involved in initiatives like PCAF “to build consensus on carbon accounting and portfolio alignment.” Barclays may produce a PCAF-aligned disclosure in the near future, but it is curious that such a prominent member of the partnership has chosen to kick off its FE reporting with its own methodology, rather than pioneering the PCAF methodology.

The examples of Scotiabank, Barclays, and others show that while PCAF has a broad reach, it may take a little more time before it convinces all firms that it is the ‘gold standard’ FE methodology to follow. On the other hand, the fact that so many banks — including the world’s biggest and most complex firms — have at least started to disclose FE in reference to the PCAF standard shows that it has come a long, long way from its humble beginnings.

Bank FE disclosures analyzed by Climate Risk Review: ABN Amro, Achmea Bank, Alternative Bank Schweiz, Amalgamated Bank, Banca Etica, BMO, Bunq, Citi, Clearwater Credit Union, CTBC, Deutsche Bank, Ecology Building Society, HSBC, Islandsbanki, Nationwide, NatWest, RBC, Scotiabank, TD Bank, Triodos Bank