The regulatory body has an explicit duty to respond to emerging threats to the stability of the US financial system. Climate change is one such threat.

US financial regulators have been playing catch up on climate risk for much of President Biden’s time in the White House. By some measures, they have made good progress since January 2021. Still, their level of activity falls short of that demanded by the urgency of the climate crisis. Worse, these regulators are not responding appropriately to the elevation of climate physical and transition risks triggered by the failure of Congress to push through meaningful climate legislation.

True, a deal on climate spending is still possible. Yesterday, Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) — a Democratic holdout on climate action who only a few weeks ago detonated his party’s clean energy plan — said he’d reached an accord with party leaders on a rejigged package that would include $369 billion for energy and climate change programs. However, plenty of procedural obstacles stand in the way of this deal becoming law — and the mercurial Manchin could of course change his mind again.

Without Congressional action, the country’s 2030 climate target — a commitment to cut emissions 50-52% by 2030 versus 2005 levels — is in jeopardy. If this target isn’t met, then certain avoidable climate risks will come to pass, while others that may have been manageable could mutate into significant threats to the US economy and financial system. This elevates the role of federal regulators, putting the onus on them to find ways to manage, mitigate, and minimize these risks.

This reality has yet to be acknowledged by US finance officials, however. Earlier this month, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen told the Washington Post that the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) — a panel of financial agency officials that she chairs — is “mainly concerned with evaluating the risks of climate change for financial stability” and is not “a direct tool to address climate change.” Her remarks stirred the ire of climate finance activists, and conveyed a false impression of the FSOC as a passive observer of systemic financial risks, rather than as a body explicitly set up to respond to such threats. They also seemed out-of-kilter with the FSOC’s own actions to date on climate change. Just last year, the body released a report on climate-related financial risk which proclaimed that climate change is an “emerging threat to the financial stability of the United States.”

Though climate change is unique among systemic risks because of its scope, scale, and time horizon, like other systemic risks it is one best dealt with at its source. This means stopping the burning of fossil fuels. Congress’ inability to achieve this legislatively does not prohibit a regulatory response. In fact, it demands one. Financial regulators have a duty to take a “precautionary approach” to climate-related systemic risk, which requires them to prevent the financial system engaging in activities that would worsen climate change. So yes, in the cause of combating climate-related systemic risk to the financial system, the FSOC is a direct tool to address climate change, no matter what Secretary Yellen says.

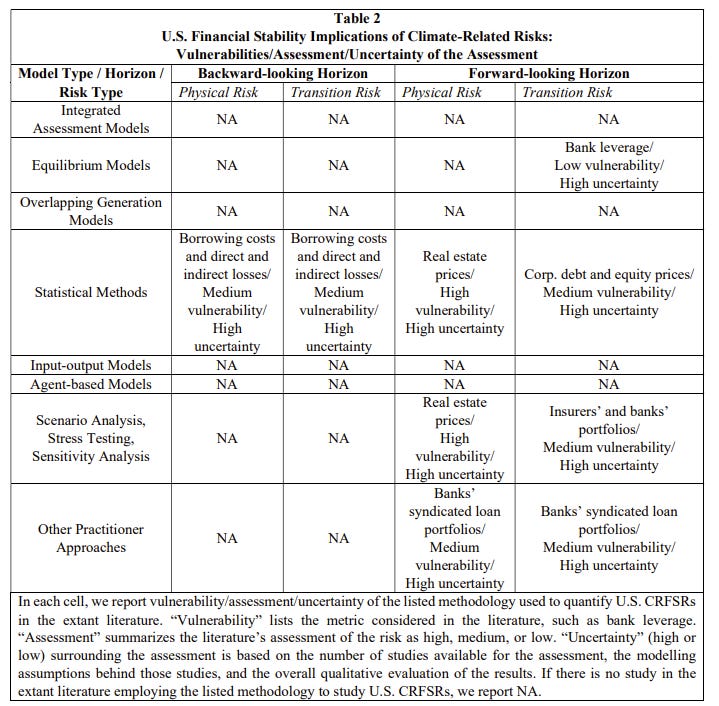

Her refusal to wield the FSOC in this way may be due to political constraints, and an understandable urge to spare officials from the caterwauling of anti-regulatory interests. But it may also be because US regulators still have a poor grip on the climate-related financial risks the country faces. This is borne out by a recent paperfrom the Federal Reserve, which rounded up the existing literature on what it calls “climate-related financial stability risks” (CRFSRs) and explored current methods and tools for analyzing them. One of the paper’s key findings is that the academic corpus on US CRFSRs is “thin” and covers “only a few” US financial system vulnerabilities. Indeed, most of the models and approaches considered in the paper have not, so far, been used to quantify US CRFSRs at all.

Source: Federal Reserve

Furthermore, the scant analysis conducted to date implies that some climate risks are nothing for US authorities to get worked up about. For example, the paper says that forward-looking assessments show that future transition risks to financial stability are “likely medium”, albeit with “a high level of uncertainty.” While physical risks to some assets, predominantly real estate, do appear high under certain methodologies, again the paper says this assessment is highly uncertain.

Regulators’ relative blindness when it comes to US CRFSRs may be blocking assertive climate action from the FSOC. Perhaps Yellen and company would feel more empowered to use regulation aggressively if they had mountains of data to back them up. But if that is the case, then FSOC agencies should be prioritizing the kind of climate stress tests and exploratory analyses pioneered by the European Central Bank, Bank of England, and the Autorité de contrôle prudentiel et de résolution. As it stands, to date only two state-level authorities — the California Department of Insurance and New York Department of Financial Services — have run climate scenario analyses of insurers under their jurisdiction. True, some federal agencies have said that climate analysis exercises are on their agenda, notably the Federal Reserve. However, Wall Street doesn’t see these happening until 2023 at the earliest.

Certainly, the Fed has a lot on its plate, and has been understaffed to boot. But with the confirmation of Michael Barr as the central bank’s new Vice Chair for Supervision, it now has the institutional resources to raise its climate game. At a confirmation hearing before the Senate Banking Committee in May, Barr said the Fed has “important but quite limited” powers to monitor the financial risks emanating from climate change. It may be an anodyne statement, but it does suggest he is open to the kind of climate scenario exercises previously floated by his now-colleague at the Fed, Lael Brainard.

The FSOC gathers for its 100th meeting today. The panel has remade itself over the last 18 months after four years of neglect under the Trump administration, and through its inaugural report on climate-related financial risk has laid the foundations for a robust US regulatory response to this emerging threat. Now is the time to build on those foundations, and build rapidly. The panel has to upgrade US climate risk modeling capabilities and produce the data it needs to empirically support a “precautionary approach.” It has to move on from the risks analysis phase and into the regulatory phase. And it has to make peace with the fact that in order to honor its remit, it does have to address climate change directly.